Our students often ask us how to say “my father is a …”. They want to describe to other people what their parents do for a living. Here is a list of all sorts of jobs – the most common ones anyway. Sometimes there is an “official word” for a profession and sometimes there is an every-day-usage word as well. We also explain the さん, or ‘san’ addition. What to do with the word さん, or ‘san’? That is quite difficult to explain, but let’s see, if we can make it clearer for you.

For example: ‘pan-ya-san’ means ‘bread-shop-person (in-charge)’, or ‘Mr bread-shop’, hence ‘baker’. If you want to say “I am a baker”, then you would say “パンやです”, “pan-ya-desu”. You would not refer to yourself, or even to your own family using the added politeness “さん”, or “san”. So, when you talk about a baker, you would say “パンやさんです”, but when introducing yourself you would say “パンやです”, “pan-ya-desu”.

This is quite important: a principal in a school would never say in assembly that he/she is “こうちょうせんせい”, or “kōchō-sensei”; he/she would say: “こうちょうです”, “kōchō desu”. The students on the other hand would speak to the principal as “こうちょうせんせい”, or “kōchō-sensei”.

In the following text we will make this idea of adding respect or showing modesty clear by adding brackets to the word “さん”, or “san”, so you would know when to leave it out.

As a final note: when you would like to talk to someone in a professional situation, you would either call out すみません, sumimasen, excuse me, or せんせい, sensei, sir/madam (teacher/doctor). Never call out さん, san (Mr/Sir/Miss), as it would be misunderstood and they would think you called out “THREE!”

In everyday usage teachers are せんせい ‘sensei’. In a classroom students call their teacher せんせい. However, the teaching professional is a 教師, or きょうし, or ‘kyōshi’, not せんせい. In other words: せんせい is the title you use for your teacher. The meaning of the word せんせい is actually ‘Elder”. The phrase にほんごの せんせい is talking about your Japanese language teacher.

Mathematics teacher

すうがく の せんせい sūgaku no sensei

university student だいがくせい daigakusei

students がくせい gakusei

Primary School students しょうがくせい shōgakusei

doctor [お] いしゃ [さん] [o] isha [san]

Note the profession is ‘doctor’, but when talking to a doctor, you call him/her せんせい, ‘sensei’. Doctor is a particularly difficult word, because it has the honorific (=very polite) prefix お added as well. This is because the position of a doctor in Japanese society is regarded very highly: ultra polite.

female nurse かんごふ [さん] kangofu[san]

male nurse かんごし [さん] kangoshi [san]

butcher にくや [さん] nikuya [san]

baker パンや [さん] panya [san]

cake shop owner ケーキや [さん] keekiya [san]

florist はなや [さん] hanaya [san]

pharmacist くすりや [さん] kusuriya [san]

tourist かんこう きゃく kankō-kyaku

cook コック [さん] kokku [san]

guests [お] きゃく [さん] [o] kyaku [san]

The word for guest is also a difficult one: again the お shows extreme respect and consideration. Sometimes in very polite company a guest is referred to as Most Honourable Guest: お客様 おきゃくさま o-kyaku-sama. Japanese hospitality is unbelievably considerate and generous. It can even be a burden on a family as they want to make the guest feel special, so they go to a lot of costs, which don’t always suit the budget – but it is impolite to complain.

housewife しゅふ shufu

主婦の友, しゅふのとも, or shufunotomo is “The Housewife’s Friend” – the Japanese equivalent of “The Woman’s Weekly” magazine. The journalistic level of the magazine is quite high though and it is most informative about matters regarding education, finances, relationships, upbringing, hobbies, cooking etc. Many Japanese housewives work part-time in a local business, thus supplementing the family income for the “extra” bits.

policeman けいかん keikan

shop assistant てんいん tenin

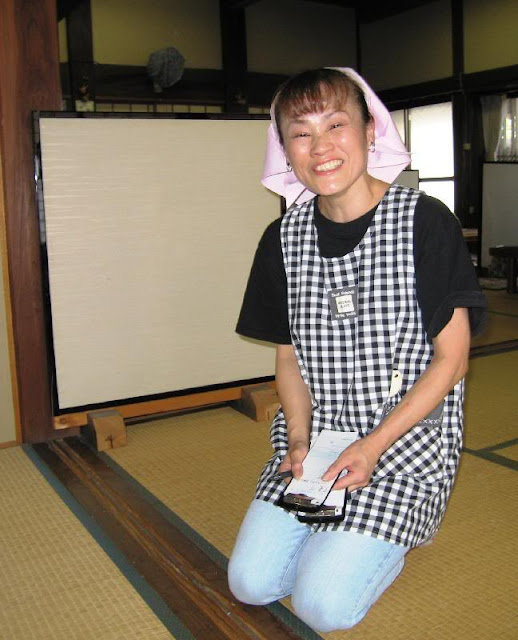

inn help りょかんの おばさん ryokan-no-obasan

Probably when you talk to the lady, you would call her おばさん, or “obasan”. Japanese courtesy, helpfulness and generosity are legendary. Her smile says it all:

” よくいらっしゃいました” - ‘You are most welcome”.

waitress ウェートレス uetoresu

waiter ウェーター ueetaa

greengrocer やおや [さん] yaoya [san]

camera shop owner カメラや [さん] kameraya [san]

fish shop owner さかなや [さん] sakanaya [san]

company office staff/employee かいしゃいん kaishain

Of course, when you talk to a かいしゃいん, or “kaisha-in”, you would call them by their surname, e.g. Mr/Mrs/Miss Tanaka, たなかさん.

The salaried worker サラリーマン, sarariiman, is a word that has been lingering in Japanese language text books. It is probably there, because it looks so “Engrish“, but it actually is not really all that polite. The word should be moved to a history book, which describes the relentlessly hard work of the office workers trying to do their thing for building up Japan 50 years ago. There never was such a person as a “sararii-uuman”. For this reason the word has gone out of usage. Really, people in a company want to be referred to as “かいしゃいん”, or “kaishain”.

managing director しゃちょう [さん] shachō [san]

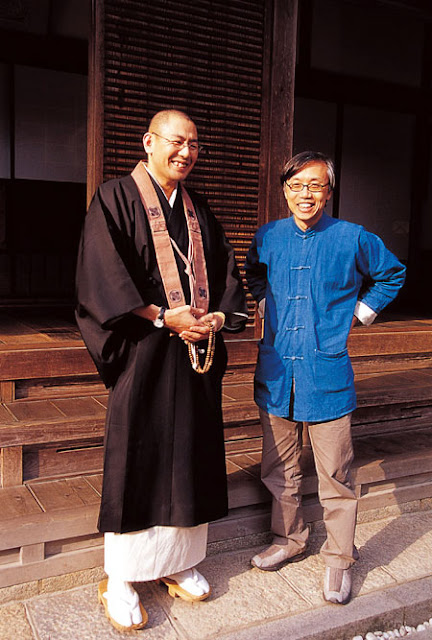

Buddhist priest [お] ぼうさん [o]bōsan

The position of the Buddhist priest in a traditional Japanese village was so respected that さん was always added. Families always own the actual temple and the land it is on. Traditionally priest families were in a privileged position – landowners. These days that is not always the case, as the State does not support the temple system. It is a family business that needs to support itself and some do so successfully, others less so. Funerals in Japan tend to be organised and performed by Buddhist priests.

Shintō priest かんぬし kannushi

accountant かいけいし kaikeishi

singer かしゅ kashu

taxi driver タクシーのうんてんしゅ takushii no untenshu

plumber すいどうや [さん] suidōya [san]

carpenter だいく [さん] daiku [san]

electrician でんきや [さん] denkiya [san]

chauffeur うんてんしゅ untenshu

bus driver バスのうんてんしゅ basu no untenshu

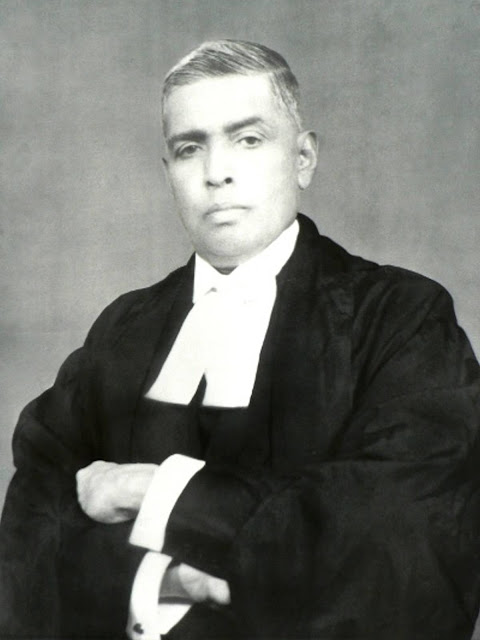

lawyer べんごし bengoshi

actor はいゆう haiyū

architect けんちくか kenchikuka

dentist はいしゃ [さん] haisha [san]

bank employee ぎんこういん ginkōin

player せんしゅ senshu

fireman しょうぼうし shōbōshi

ambulance driver

きゅうきゅうしゃのうんてんしゅ kyūkyūsha no untenshu

unemployed person しつぎょうしゃ shitsugyōsha

protestant minister ぼくし bokushi

Officially the officer is a けいかん, or “keikan”, but little children still call him or her おまわりさん. Here the officer is delivering a keep-yourself-safe programme at a school: the sign reads “traffic safety”.

judge さいばんかん saibankan

real estate agent ふどうさんや [さん] fudōsanya [san]

tatami shop owner たたみや [さん] tatami-ya [san]

internal link to Tatami:

air hostess スチュワーデス suchuwaadesu

pilot パイロット pairotto

manager マネージャー maneejaa

ladies’ hairdresser びようし biyōshi

men’s hairdresser りようし riyōshi

bookshop owner ほんや [さん] honya [san]

fisherman りょうし ryōshi

farmer [お] ひゃくしょう [さん] [o]hyakushō[san]

cleaner そうじふ [さん] sōjifu [san]

launderette owner せんたくや [さん] sentakuya [san]

homeless person ホームレス hōmuresu

Of course, this word is used only when describing this person’s circumstances, never when talking to the person.

The homeless people of Japan are relatively few for such a huge population. Their reputation is one of “never bothersome”. Nevertheless, their presence shows the “underbelly” of Japanese society – clearly not everyone is a winner. Each and every case seems to have a lengthy, tragic story behind it. In western and in other Asian and African societies the homeless condition is much worse. There are Japanese government support organisations and some private organisations and some Great Souls who tirelessly work for these people’s care: they are society’s unsung heroes.

librarian としょかんいん toshokan-in

pupils せいと seito

pro-rata workers アルバイト arubaito

[minimum-wages-by-the-hour workers; from the Dutch word Arbeid = physical work]

secretary ひしょ hisho

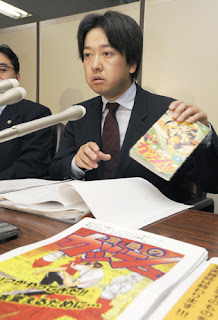

cartoonist マンガか mangaka

photographer しゃしんか shashinka