Category Archives: Mirai 2-061

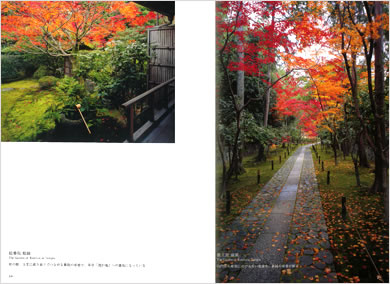

Autumn in Japan

Water feature in traditional Japanese garden, つくばい, tsukubai

つくばい tsukubai

つくばい tsukubai

つくばい tsukubai

つくばい tsukubai

つくばい tsukubai

つくばい tsukubai

つくばい tsukubai

つくばい tsukubai

つくばい tsukubai

つくばい tsukubai

つくばい tsukubai

つくばい tsukubai

つくばい tsukubai

つくばい tsukubai

つくばい tsukubai

つくばい tsukubai

つくばい tsukubai

つくばい tsukubai

つくばい tsukubai

つくばい tsukubai

つくばい tsukubai

つくばい tsukubai

つくばい tsukubai

つくばい tsukubai

つくばい tsukubai

Who is wearing what?

To wear in Japanese

Australian Animals オーストラリアの動物 オーストラリアのどうぶつ

Heian Era 平安時代 へいあんじだい

Heian Era 平安時代 へいあんじだい heian jidai

Heian Era 平安時代 へいあんじだい heian jidai

The Heian Period was a time period when the Imperial Court lived in great splendour and opulence. The common people did not, of course.

Heian Era 平安時代 へいあんじだい heian jidai

Heian Era 平安時代 へいあんじだい heian jidai

Heian Era 平安時代 へいあんじだい heian jidai

Heian Era 平安時代 へいあんじだい heian jidai

The dolls represent courtly ladies who would be busy all day long talking about poetry, silk, hair dressing, make-up, children, men and status, and gossip and other equally important matters. Although every so often a lady would rise in fame because of her personality, her birth rank and her talents.

Hundreds of years ago, one of these courtly ladies, the Lady Murasaki, has been credited with writing the first novel in history. Also, over a period of time courtly ladies were the first women to develop the hiragana handwriting script, as a sort short-hand version of Chinese kanji.

Heian Era 平安時代 へいあんじだい heian jidai

Heian Era 平安時代 へいあんじだい heian jidai

These photos were taken during various Kyoto Festivals all celebrating the glorious past of the Imperial Court and the aristocracy. We doubt there is a festival celebrating the Age of the Wretched Common Worker. Never mind – it’s colourful.

Each layer of kimono indicates a higher status level. Layers could be counted on the arm and around the neck. Mind you, to be realistic, if you were in the presence of a person who wore such an elaborate kimono, you would either wear one yourself, or you would be a servant. Either way, you would already know the other person, so you wouldn’t have a need to count kimono layers. Imagine that these days Queen Elizabeth II would have to explain to her guests that the glittering stones on her head are actually diamonds!

Here is a link to a support page:

A whimsical tansu たんす

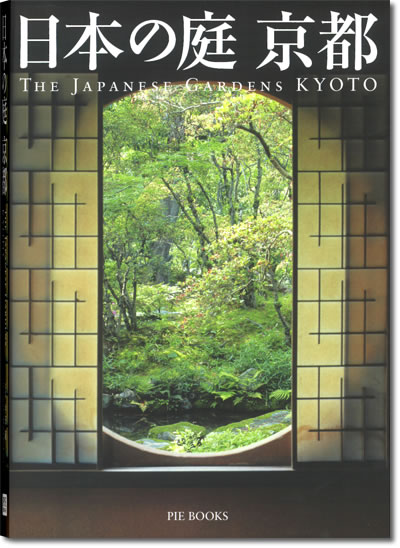

Gardens 庭 にわ

Farming 農業 のうぎょう 牧畜業 ぼくちくぎょう

Farming (agriculture)

農業 のうぎょう nōgyō

Farming (animals)

牧畜業 ぼくちくぎょう bokuchikugyō

The main problem with the two words is that the translation doesn’t work all that well. The reason is that although the Japanese language does have two words to describe the ideas, the reality is that farming methods in the USA, Canada, Australia and even New Zealand, or South Africa, are so vastly different that a Japanese farmer would first have to see it to believe it.

Whereas a Japanese farmer may be very wealthy with 20 cows, a Canadian farmer may have up to 5000 cows. Whereas a Japanese farmer may have 3 acres of personally tended land, an Australian farmer may have up to 10000 acres. Whereas a Japanese farmer may plant 3 acres with individual rice plants, an Australian or American farmer may sprinkle the rice grains from a plane over some 4000 acres.

The scale of operation is so different, that a Japanese farmer could hardly imagine it. These ideas do not even take into account that Australian farms have enormous droughts and floods, while Japanese farmers may have a monsoon, or an encroaching city as problems. Brazilian farms may have tropical problems.

Consequently Japanese people living outside Japan tend to use local words in transliteration , e.g. “faamingu” and “faamu”, because the proportions become immediately clear.

The words “my father is a farmer” become problematic.

Outside Japan the best translation would be “my family has a farm”,

i.e. うちはファームです。

uchi wa faamu desu

My family has a farm.

or

うちはのうかです。

uchi wa nōka desu

My family is a farming family.

or

うちはのうぎょうをしています。

uchi wa nōgyō o shite imasu

My family does farming.

In Brazil they would probably use Portuguese words and in South Africa they would use Afrikaans, Bantu, or Xhosa words when speaking Japanese – a mixing of two cultural ideas and circumstances.

You must be logged in to post a comment.